Log 9

Justin

Vandenbroucke

justinv@hep.stanford.edu

Stanford

University

1/30/03 –

2/3/03

This file contains log entries summarizing the results of

various small subprojects of the AUTEC study. Each entry begins with a date, a title, and the names of any

relevant programs (Labview .vi files or Matlab .m files – if an extension is

not given, they are assumed to be .m files).

1/30/03

New contours for extreme size ranges

plotDetectionVolumeRect.m, for mode =

extraLarge and tiny

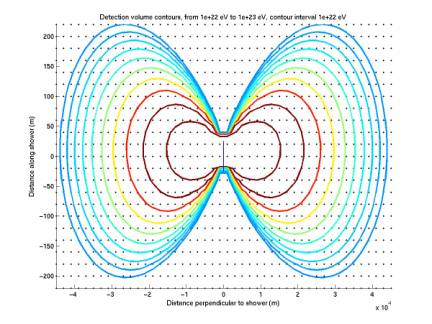

The

two plots below extend the range of our acoust radiation detection contours for

various energy values. All

contours are for threshold 0.05 (roughly the mean), but we only include up to

0.02 in our flux limit calculation.

The

first plot spans 40 km radius and 400 m width, and gives energy contours from

1022 eV to 1023 eV.

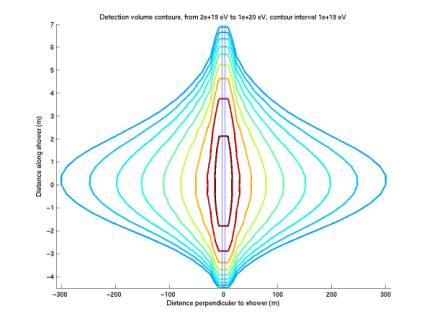

The

second plot spans 300 m radius and 10 m width, and gives energy contours from 2

x 1019 eV to 1020 eV.

Figure 1

Figure 2

1/30/03

Large-scale bathymetry within a few km of our

detector

site3Bathymetry.m

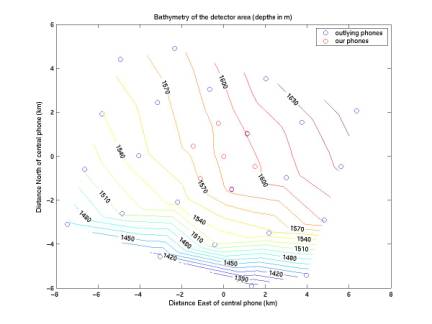

The

plot below gives depth contours for the phones surrounding our detector. Jack sent me the coordinates by email

on 1/28/03. He’s since also sent

coordinates for phones to the East and South, but I haven’t yet plotted them.

The

curves are useful for giving the general slope of the sea floor, but tell us

nothing about how rough it is on a smaller scale. There could still be bumps of up to a couple dozen meters

spanning ~ 1 km. These could block

a significant amount of our effective volume.

Figure 3

2/2/03

New acceptance curves

plotAcceptanceAllArrays.m

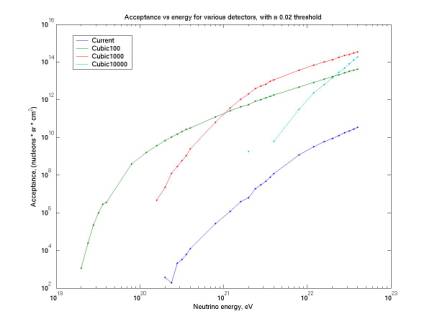

The

plot below gives acceptance curves for our current detector as well as for 3

possible cubic configurations of 10 x 10 x 10 phones, with phone spacing of 100

m, 1000 m, or 10000 m.

The

acceptance is for a 0.02 threshold, the low (quiet conditions) threshold used

most for our flux limit.

The

lower ends of the curves are the lowest energies for which we have nonzero

acceptance for each array. This is

determined by the requirement that we hit 4 phones: below this energy the

acoustic radiation does not span enough area to cover 4 phones, even in ideal

orientation. The upper ends extend

indefinitely, as long as we have infinite water.

Figure 4

2/2/03

Depth profile

depthProfile.m

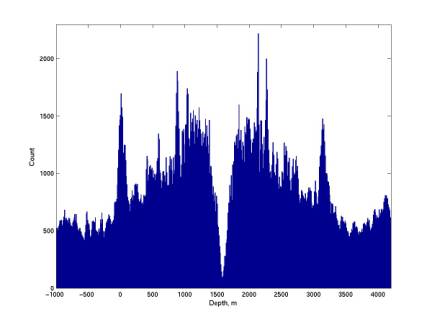

The

plot below gives the distribution of reconstructed event depths (perpendicular

to the sea surface, not the sea floor / detector). All combinations are shown, most of which are not physical

(because of our unstable event rate, we often have many combinations of events

within the coincidence window).

The non-physical events extend to large tails on both sides. The sea surface is at 0 m, the sea

floor at 1600 m. The distribution

is symmetric about the sea floor because the reconstruction algorithm cannot

distinguish between a location and its mirror about the sea floor (because the

detector is planar). Both points

are solutions to the hyperboloid intersection. There is an excess of events at the sea surface, perhaps due

to surface noise (wind, waves, rain).

The

sharp decrease at the sea floor is disturbing because this is our effective

volume. I see threee possible

explanations: (1) blocking by hills of the floor; (2) systematic error in the

hyperboloid intersection method; (3) an actual decrease in (biological?) noise

sources.

Figure 5

2/2/03

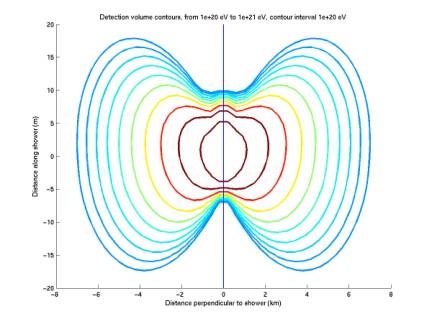

New acoustic radiation contours

plotDetectionVolumeRect.m, mode = small02

The

contours below are for a threshold of 0.02 (not 0.05 as all others are). Contours are given for 1020

to 1021 eV, our most interesting range.

Figure 6

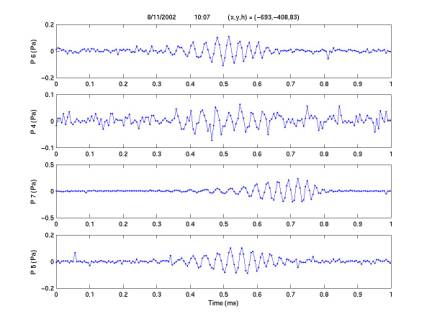

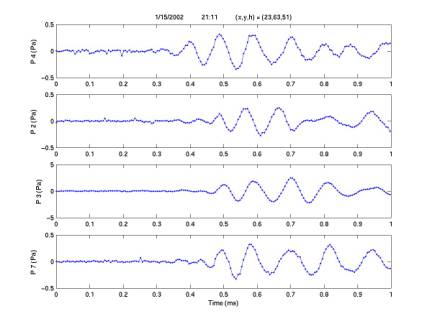

2/2/03

Examples of rejected events

plotCandidates.m

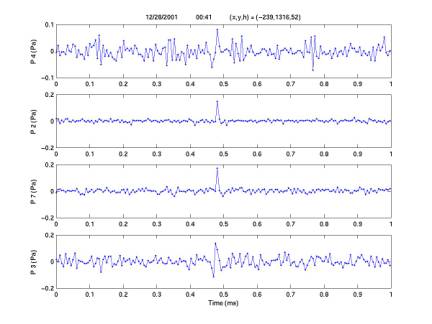

The

events plotted below are examples of our 138 candidates within 100 m of the sea

floor, during minutes with threshold < 0.025, with characteristic number of

periods < 4. Signals are given

for 4 channels, with the channel number on each y axis. In the title bar are given date, time

of day, and coordinates in m (x, y, h) = (East of center phone, South of center

phone, height above sea floor).

The

three events are of the following types: diamond (dolphin?), ping (freq ~ 10 kHz),

spike (single-sample displacement).

Note:

often one of the 4 signals is distinguishable of one of these types and another

is of another type. These events

are rejected, even if one type is tripolar (consistent with neutrino waveform),

because they are considered to be random coincidences not corresponding to the

same original source.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

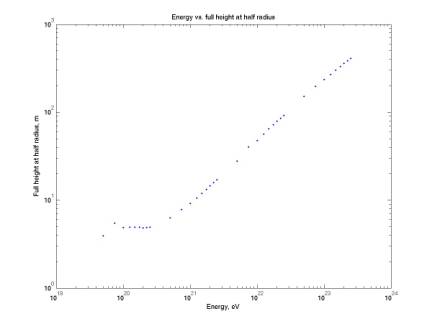

2/3/03

Radiation dimensions as a function of energy

calcDiskDims.m

plotDiskDims.m

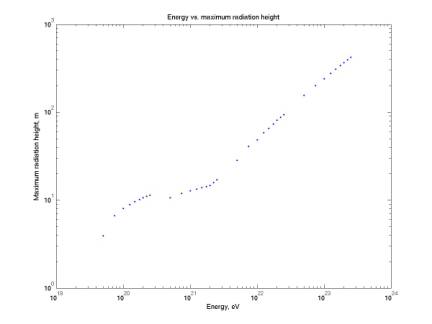

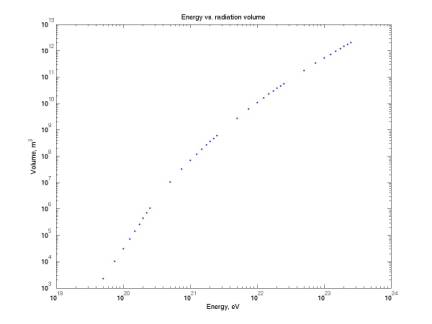

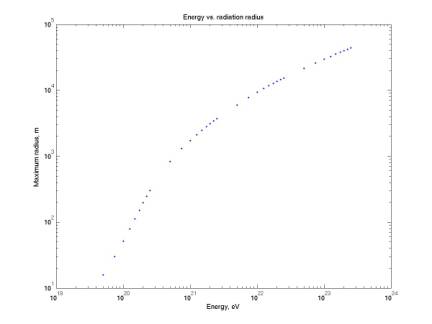

The

four plots below give the dimensions of the acoustic radiation for a threshold

of 0.02 (Note: this is not equal

to the effective volume dimensions of the detector). Height is measured along the incident neutrino axis, radius

perpendicular to this axis.

The

radius, and hence the volume, curve bends to a lower slope at ~ 1 km. This is presumably due to a change of

radiation region relative to the source, but I have not yet squared this with

Learned’s paper.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

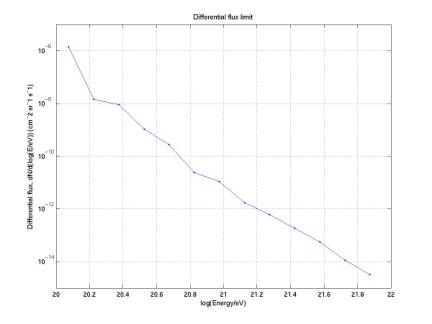

2/3/03

New flux limit

calcLimit2.m

The

plot below gives our differential flux limit, calculated by the new method

Giorgio and I agreed upon:

F(E) = integral flux = flux of neutrinos of energy

> E (cm^-2 s^-1 sr^-1)

X(E) = integral exposure = our exposure for neutrinos

of energy > E (cm^2 s sr)

N(E) = integral

number = number of neutrinos we detect that have energy > E

Then N(E) = F(E)

* X(E), so F(E) = N(E) / X(E). We

can calculate F(E), and it's actually our flux limit, but it's

integral.

So we just differentiate it, numerically, to get a differential

flux. N(E) will be calculated from

a table for Poisson rates for a given confidence level, but it does not change

much, so the differential flux is phi(E) ~ -N(E) * d[1/X]/dE. Note the negative sign (the flux is

actually the absolute value of the derivative, and 1/X is decreasing).

Here

I have assumed N(E) is constant, N(E) = 5 for all energies. I will replace this with actual values

(expected to be between 2 and 5 depending on the energy) once we are confident

of our final candidates and their energies.

Our

acceptance will not grow signifantly at higher energyes than 1022 eV because

the effective volume hits the shore (I have allowed it to grow significantly

beyond the instrumented volume for the purpose of the limit, but I would not

use this volume for actual event reconstruction if events were detected within

it). We need to decide exactly

where to cut our volume off.

Figure 14

2/3/03

Example acceptance calculation

calcAcceptanceMC.m

plotAcceptance.m

plotAcceptanceVsE0.m

Here

I walk through an estimate of acceptance at 4 * 1021 eV with a 0.02

threshold. It’s calculated by

Monte Carlo code as follows: first we choose reasonable bounds on x, y, z,

theta, and phi (theta is 0 to thetaMax, which increases with energy; phi bounds

are always 0 to 360 degrees). Then

we choose random random points in these 5 coordinates (points chosen uniformly

in all but theta; theta chosen appropriately for isotropic flux: see http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SpherePointPicking.html).

For 4 * 1021

eV with a 0.02 threshold, x and y are chosen in –5000:5000 m, z in –125:125 m,

theta in 0:2 deg = 0:0.03 rad).

This gives a total integration volume (in the 5D coordinate space) of

2*pi*(0.03)2*(1e4 m)2*(250 m) = 108 m3

sr. To convert units, we multiply

by the cross section and the number of nucleons per volume: (108 m3

sr) * (6e29 / m3) * (2e-31 cm2) = 1e7 cm2

sr. Now in our Monte Carlo code,

only ~ 1 in 103 points in our 5D coordinate space hit 4 phones or

more. So our actual acceptance for

4 phones is 1e7 cm2 sr * 1e-3 = 1e4 cm2 sr, which matches

the value in the acceptance plot above.

2/3/03

Candidate event energy reconstruction

reconstructE0.m

I

reconstructed initial neutrino energy for each of our two neutrino candidates,

using Learned’s eqn. 23. Using

this equation (integral of pressure-squared, scaled and attenuated properly),

we get an energy reconstruction from each phone’s signal (and distance to

reconstructed source). Here I

report the mean and standard deviation among the four energy measurements

(events are numbered within the final 138 candidates):

Candidate 1: (6 ± 4) e20 eV

Candidate 104: (4 ± 3) e20 eV