Log

10

Justin

Vandenbroucke

justinv@hep.stanford.edu

Stanford

University

2/8/03

This file contains log entries summarizing the results of

various small subprojects of the AUTEC study. Each entry begins with a date, a title, and the names of any

relevant programs (Labview .vi files or Matlab .m files – if an extension

is not given, they are assumed to be .m files).

2/8/03

Quiet livetime

quietLivetime.m

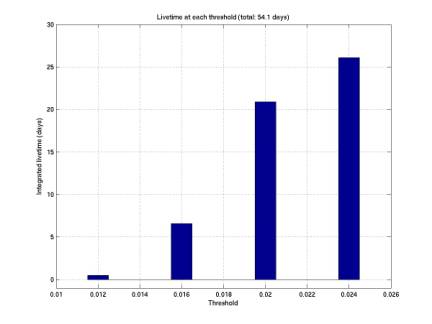

The

plot below gives the left-hand tail of our threshold livetime

distribution. These are the quietest

periods, and only these values are used to calculate our limit. Note that there are only 4 discrete

thresholds present (the thresholding algorithm steps in multiples of 0.004). For each threshold the total livetime

(summed over all minutes with that threshold) is given. The total amount of quiet (threshold

< 0.025) livetime is about 1/3 of our total livetime.

Figure 1

2/8/03

Flux limits for interactions and neutrinos

calcLimit3.m

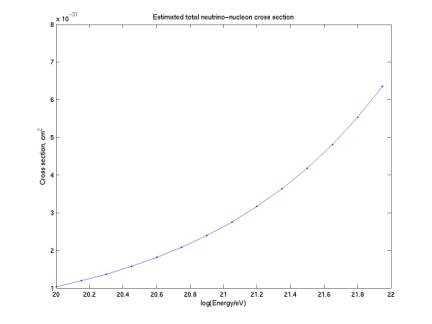

The

first plot below gives the cross section used (an extrapolated power law from

Gandhi et al) for our neutrino flux limit.

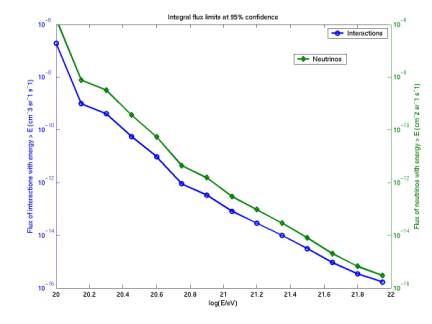

The

second plot gives integrated flux limits, both for interactions (per unit

volume per unit time per steradian) and for neutrinos, assuming all

interactions are neutrinos. The

difference between the two is that the neutrino limit incorporates the nucleon

density of water (6e29 m-3) and the cross section (as shown in the

first plot).

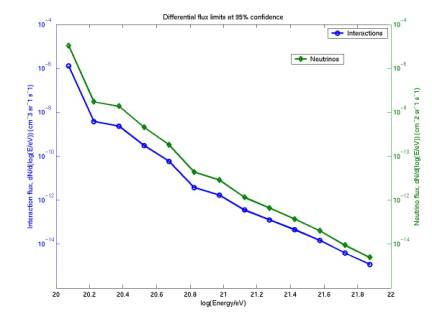

The

third plot gives differential flux limits, also for both interactions and

neutrinos.

The

limits are calculated as follows: N(E) = X(E) * F(E), where N is the number of

events detected, X is our exposure, and F is the flux (all quantities

integral). Exposure is calculated

first for each threshold independently: it is the acceptance at that threshold

times the livetime at that threshold.

X is then our total exposure, the sum over all four thresholds. For generic interactions acceptance is

in m3 sr, and for neutrinos it is this value multiplied by nucleon

density and cross section. This

multiplication is done before inverting and differentiating the integral flux

to determine the differential flux.

The

integral flux is simply F(E) = N(E) / X(E). The differential flux, dF/dlog(E/eV), is then calculated by

numerically differentiating F(E) with respect to log(E/eV). Note that F is nearly equal

dF/dlog(E/eV).

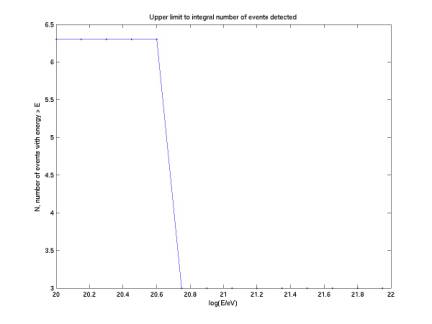

The

fourth plot gives N(E), determined by a table of upper limits at 95% confidence

for a Poisson process with 0, 1, or 2 events observed in a small time. The two events we have seen are at

nearly equal energies on this log scale.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

2/8/03

Limited bathymetry

allBathymetry.m

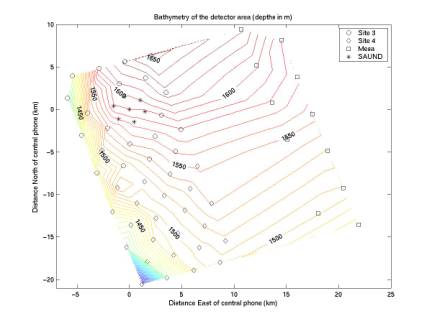

The

two figures below give rough bathymetry from the 62 phone coordinates that we

have. Depth contours are linearly

interpolated from hydrophone depths.

The

first figure gives literal depths (direct depths from the surface, not

ellipsoid heights, which are also availble).

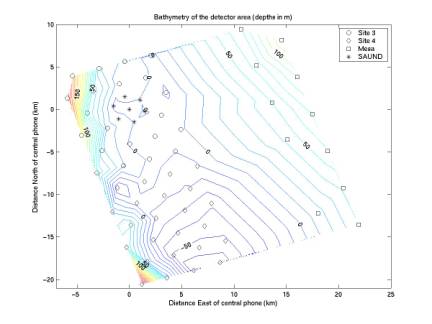

The

second figure gives sea-floor heights normal to the SAUND plane, where the

SAUND plane is defined to be the least-squares plane fit to our 7 hydrophones

(inclined at 1 degree from the horizontal). In this figure it is apparent that the floor curves up around

our phones, cutting off our effective volume. However the data are insufficient to determine the entire

shape of our effective volume. It

would be best to have these data out to at least 10-20 km from our central

phone. It would also be best to have

sufficient resolution to determine if any hills in the sea floor are blocking

our effective volume.

Figure 6

Figure 7

2/8/03

Limitations of our triangulation

variableT.m

variableC.m

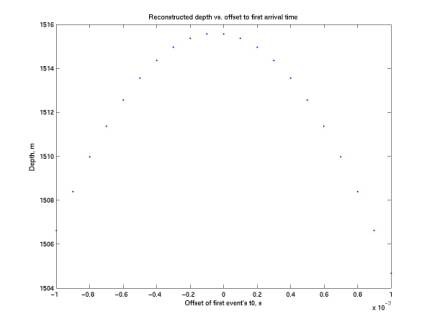

Our

triangulation method (intersecting hyperboloids) assumes no error in phone coordinates,

signal times of arrival, or sound speed.

It also assumes spatially constant sound speed. The first plot shows the effect of

timing uncertainty on our depth determination. The depth is determined with various offsets (up to 1 ms,

quite a large offset) added to the first time of arrival. We see that the depth determination is

not sensitive to this uncertainty.

The

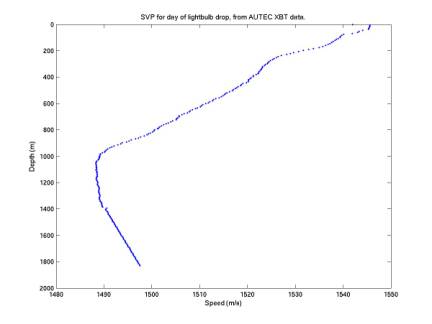

second plot shows the sound velocity profile (SVP) for the date of our light

bulb drop, July 30 2001. These

SVP’s should be available for many days from an FTP site but I’m

waiting to hear from an AUTEC employee about obtaining them.

We have been

assuming a sound speed of 1516 m/s, constant throughout depth and over seasons,

but our depth determination turns out to be quite sensitive to sound

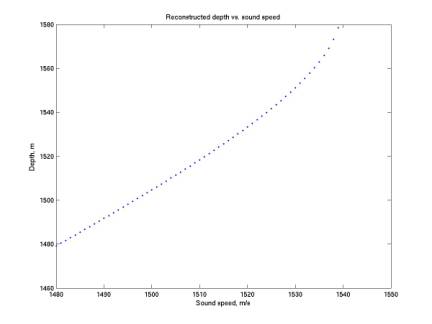

speed. Assuming the second plot

(with sound speeds ranging from 1480 to 1550 m/s) is the appropriate curve for one of our candidate neutrinos,

we plot in the third figure the reconstructed depth as a function of a

particular (constant over depth) sound speed in this range. The depth uncertainty turns out to be

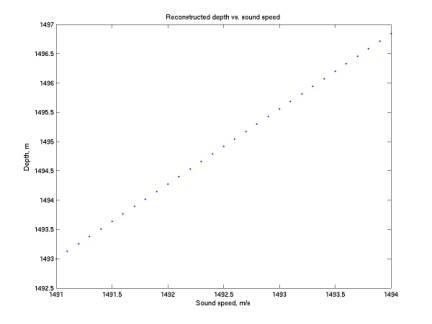

100 m. However we can iterate this

procedure again: we can focus on sound speeds that occur in this 100 m depth

range, a much narrower range of speeds (1491 to 1494 m/s). Applying this range of speeds gives a

range of depths of only 4 m.

This is a

particularly good case because the event is near the sea floor: for events near

the sea surface the entire SVP must be considered. But this is okay for us because we are primarily interested

in events near the floor.

If we have

SVP’s for many days throughout the year, hopefully we can apply this

method successfully and continue to use one effective speed for each

triangulation. It should be

possible to determine this from the reconstructed-depth profile once we obtain

the SVP’s. It would be much

more difficult to consider the sound speed varying over depth for each

triangulation, as the soultion would not be trivial and w have to calculate

hundreds of thousands of triangulations for our current data set.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11