Log

14

Justin

Vandenbroucke

justinv@hep.stanford.edu

Stanford

University

3/20/03 –

This file contains log

entries summarizing the results of various small subprojects of the AUTEC

study. Each entry begins with a date,

a title, and the names of any relevant programs (Labview .vi files or Matlab .m

files – if an extension is not given, they are assumed to be .m files).

3/20/03

Ray tracing

rayTrace.m

I

have been neglecting ray refraction because earlier I determined it was

insignificant for a range of a couple km.

But if we want an effective volume stretching to 10 km, we need to check

ray paths at that range. With this

range, ray bending becomes significant.

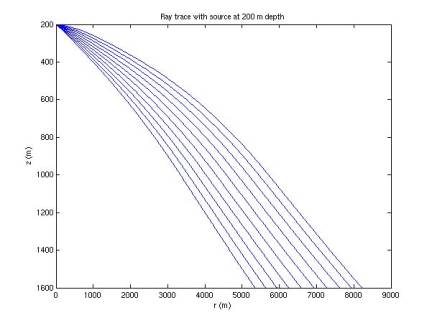

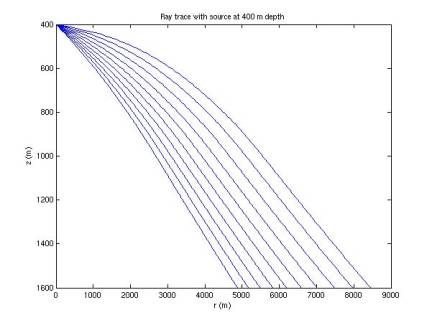

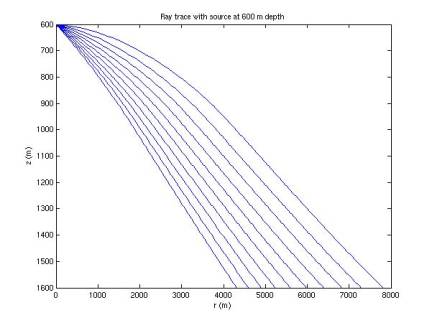

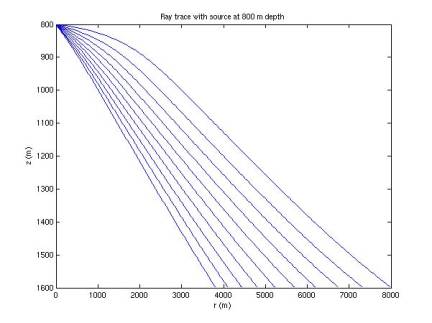

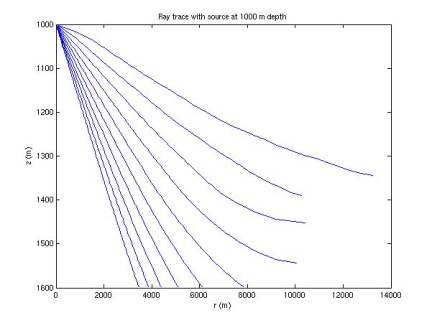

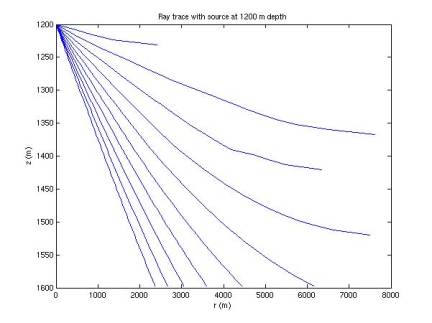

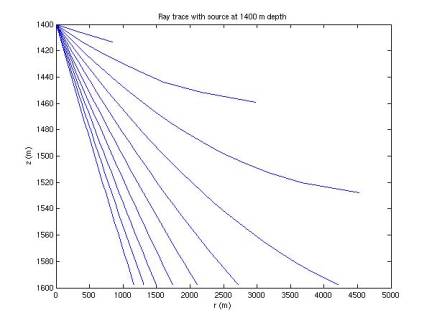

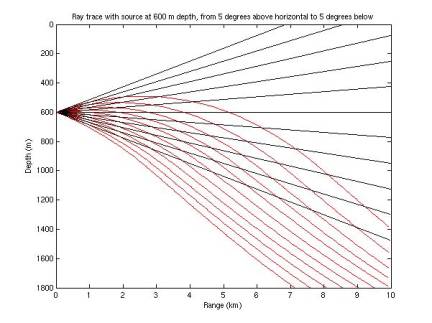

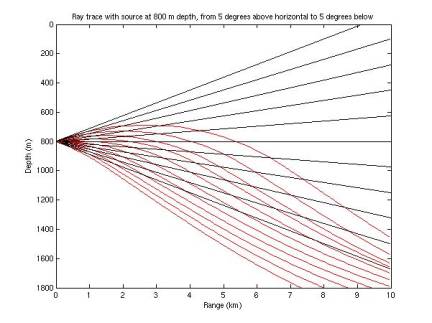

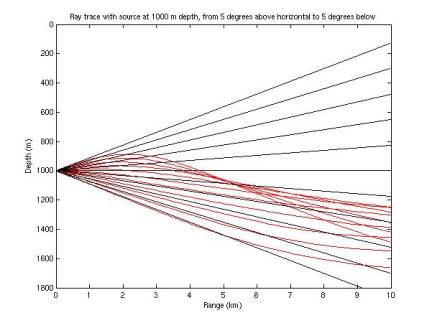

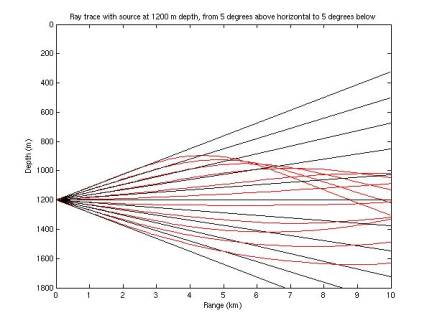

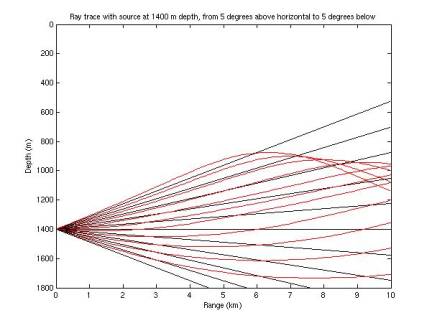

In Figures 1-7, 10 rays are simulated at each of 7 depths. Rays are emitted at an angle below the

horizontal from 1 to 10 degrees, with a step size of 1 degree.

The

ray traces are rough estimates with an initial algorithm that will be

improved. When the rays begin to

curve back upward, they are cut short. The deeper the source is, the more the rays tend to bend back

upwards, limiting the horizontal range they can travel. This introduces a shadow: near the sea

floor our horizontal range is limited, with the range increasing with height

above the sea floor.

The

ray trace assumes the water is a layered medium, with sound speed varying only

in the z direction. According to

Gerald D’Spain at Scripps, horizontal sound speed gradients are typically

3 orders of magnitude below vertical gradients.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

3/20/03

Refraction shadowing

calcShadow.m

plotShadow.m

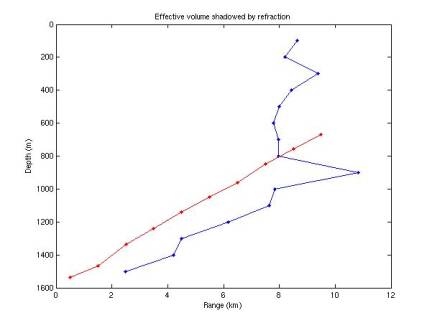

So

ray tracing shows that refraction introduces a shadow, blocking events in some

parts of the water from being heard.

Unfortunately this shadow seems to correspond well with our effective

volume. Figure 8 shows the shadow

(blue curve). Only events above

the blue curve will be detected; rays from events to the right of the curve

will be refracted away from the detector. The red line gives the bounding curve for our effective

volume assuming no refraction, due to the shape of the radiation disk, for

2.4e22 eV (the volume ceases to grow near this energy). Our actual effective volume is then

bounded by the two curves.

However

it may be the case that the overall effects of refraction are to bend the

effective volume upward rather than blocking it. If we fully account for refraction, the red curve may be

bent upward. We need to simulate

the radiation disk including the effects of refraction to determine this (such

a simulation will depend on the orientation of the disk in the water). We may be able to do this simply by

considering a surface of the radiation pattern and bending each point on it

appropriately (ie we wouldn’t have to repeat the entire simulation).

Figure 8

3/20/03

Improved ray trace algorithm

traceRay.m

rayTrace.m

plotRays.m

Following

conversation with Gerald D’Spain at Scripps, I devised an improved ray

trace algorithm that allows significantly better precision with a given CPU

time. The algorithm is explained

in Boyles, Allan: Acoustic Waveguides: Applications to Oceanic Science. It divides the water column into layers

and assumes that the sound speed is a linear function of depth within each layer. This is a much better approximation

than the previous one, which assumed the sound speed was constant in each

layer. Indeed, the AUTEC SVP is

well approximated by a 2-piece linear function, with the first piece linearly

decreasing with depth and the second part linearly increasing. This is the case in many ocean columns.

In

a medium with a constant-gradient sound speed, the ray paths can be shown to

follow the arc of a circle with radius determined by the mean sound speed and

the sound-speed gradient. The new

ray trace algorithm, traceRay.m, uses this feature in each layer. The layers can be chosen denser in

regions where the SVP is farther from linear. Arcs are calculated through each layer, but only the

endpoints are saved. Ray paths are

then drawn with each arc replaced by a straight segment, giving an allusion of

less accuracy than is actually achieved.

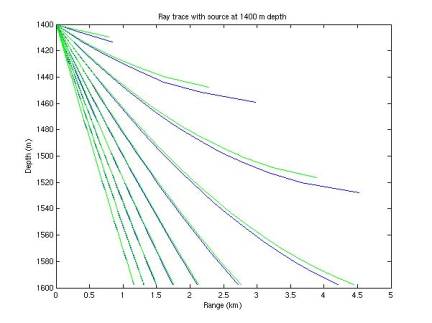

Figure 9 compares the old algorithm (blue) to the new one (green) for a

particular source depth.

Figure 9

3/20/03

Direct determination of refraction shadowing

raysFromPhone.m

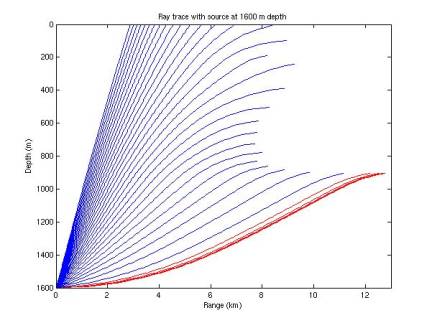

We

can determine the region shadowed by refraction directly by considering rays

emitted from a hydrophone. These rays are the same as those that

would be sent to the phone from a

source. In Figure 10, rays are

emitted from a phone at 1600 m depth at an angle above the horizontal from 1 to

30 degrees, every 1 degree (blue).

Rays are also emitted at an angle of 10-1 through 10-10

(every factor of 10) degrees to show the asymptotic boundary of the shadow

region (red).

Rays

are terminated when they reach the horizontal and begin to turn around (beyond

this point they follow the reflection of their first path. We can compare the shadow region in

Figure 10 (all white space to the right of the traces) with the indirect

determination in Figure 8 (blue curve).

In

general, if a ray is emitted horizontally, it will travel toward the sound

speed minimum (at 1100 m in our case) and then turn around where the sound

speed increases again to the value where the ray originated. The ray continues to oscillate between

these two turning points.

Figure 10

3/25/03

Full ray trace compared to

straight paths

plotRays.m

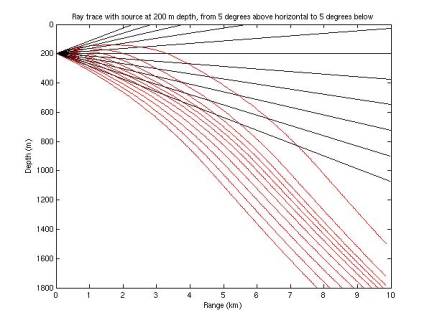

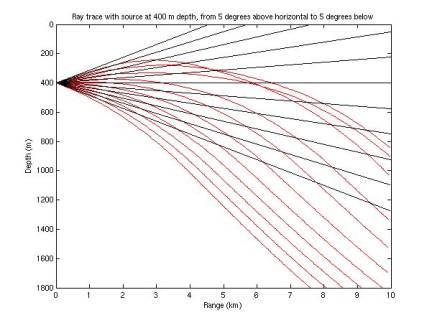

I

extended the ray tracing algorithm to continue tracing the rays when they

reverse vertical direction. In

Figures 11-17, red rays represent those determined by ray tracing; black rays

represent the case of zero refraction.

Recall the sound speed minimum is at ~1100 m. Rays are terminated when they hit 0 depth, 1800 m depth, or

a total path length of 10 km.

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

3/25/03

Effect of refraction on acoustic radiation disk

plotDiskVertices.m

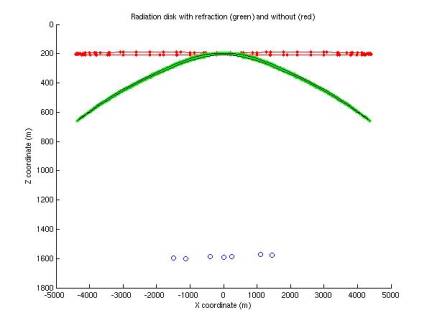

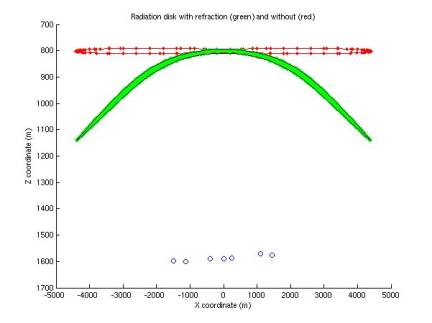

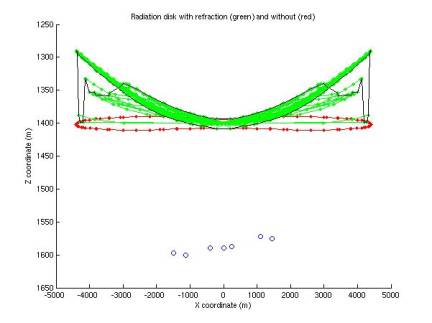

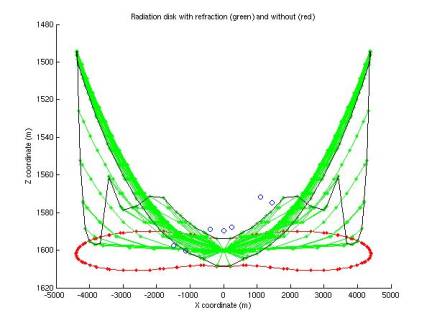

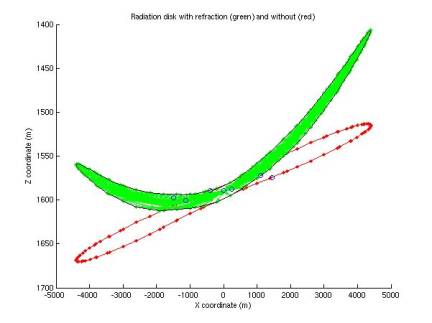

Refraction

affects the acoustic rays from a neutrino shower, bending the equal-amplitude

surface enveloping the radiation pattern.

We can determine the correct radiation pattern by starting with an

unbent disk and bending a sample of rays that terminate on the disk. This is done for horizontal disks

(vertical neutrino incidence) in Figues 18-22 for various interaction depths

(200, 800, 1000, 1400, and 1600 m).

In each plot the original and bent disks are drawn, as are the 7

hydrophones. A black curve

connects neighboring ray endpoints to sketch the envelope of the radiation

pattern.

Above

the sound speed minimum (at 1100 m), the disk is bent downward; below it the

disk is bent upward. At depths

near and below the sound speed minimum, there are some special rays that leave

the group. The flux of these is

low, however, indicating the amplitude is correspondingly decreased.

Figure

23 shows an example of a refracted disk that actually contains multiple hydrophones. The neutrino interaction is at depth

1590 m and zenith 1 degree.

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23