Log

15

Justin

Vandenbroucke

justinv@hep.stanford.edu

Stanford

University

3/28/03 –

This file contains log

entries summarizing the results of various small subprojects of the AUTEC

study. Each entry begins with a

date, a title, and the names of any relevant programs (Labview .vi files or

Matlab .m files – if an extension is not given, they are assumed to be .m

files).

3/28/03

Ray trace bug fixed

traceRaySetLength.m

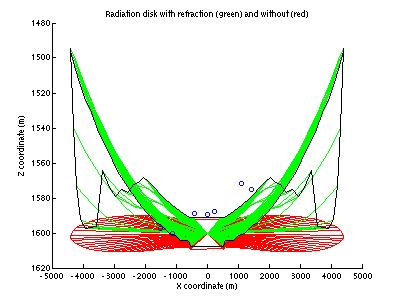

The

bent radiation had some rays (those near the horizontal) that diverged from the

others, as shown in Figure 1. This

caused the envelope of the radiation disk (black line, connecting successive

ray endpoints) to have a strange shape.

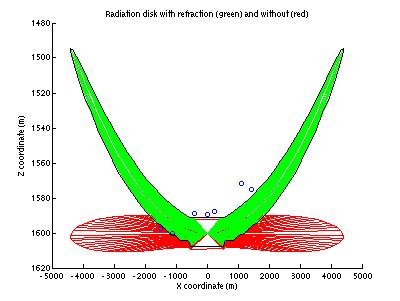

This

was due to a bug in determining the ray turning points. I was interpolating depth as a function

of sound speed, but this function is double-valued from 900 m to 1800 m. Choosing the appropriate branch before

interpolating fixed the ray tracing (Figure 2).

Both

unbent (red) and bent (green) rays are plotted on the right and left sides from

only 1 degree above the horizontal to 1 degree below, every 0.02 degrees. The disk is well determined by this

small range, meaning it only spans ~2 degrees.

Figure 1

Figure 2

4/2/03

Calculation of

acceptance without

refraction

calcAcceptanceMC.m

plotAcceptance.m

calcAcceptanceVsE0.m

plotAcceptanceVsE0.m

plotDiskVertices.m

The

detector acceptance must be recalculated now that we realize refraction is a

significant effect. As shown

above, the radiation disk curves on the same distance scale as the detector, meaning

that a radiation disk of radius 10 km that is 7 km away from the array,

coplanar with the array, will not necessarily trigger the phones (it may curve

away before reaching the phones).

The

acceptance calculation accounting for refraction is significantly more involved

than when we neglected refraction.

From Nikolai’s simulation of the signal at arbitrary receiver

positions relative to the neutrino, we have the envelope of the radiation disk

for a given neutrino energy and filter-value threshold.

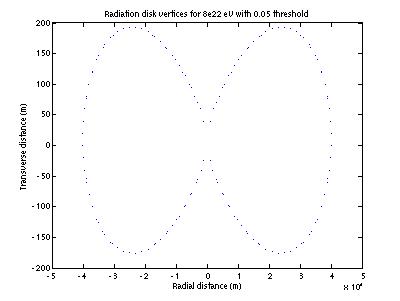

This

disk is defined by a set of O(100) vertices in 2D, such as that in Figure

3. The disk is a surface of

revolution about the vertical axis of the figure. The vertices are symmetric about the y axis. For points with nonzero x, each pair of

vertices with equal y coordinates determines a circle, about the y axis, of the

radiation disk surface. The

surface is thus defined by a set of circles.

Figure 3

In

general, to calculate acceptance at a particular neutrino energy we choose

random neutrino shower coordinates (x, y, z, theta, phi). We then count the number of phones that lie within the radiation disk,

as defined by the set of circles.

We do this phone-by-phone, determining one-by-one whether each phone is

inside the disk.

In

the case of no refraction, the ocean is isotropic and rather than having to

rotate the radiation disk to (phi, theta) we can equivalently leave the disk

fixed and rotate the phone appropriately.

This is conceptually and computationally much easier.

We

really only care about the axis between the neutrino interaction point

(idealized to a point at the center of the radiation pattern) and the

phone. The question is on which

side of the phone the disk cuts through this axis. We determine this by choosing any plane containing the axis.

We

choose the plane that is perpendicular to the radiation disk. With this choice, the intersection of

the plane and the disk is simply the 2D set of vertices shown in Figure 3. So we need not manipulate these vertices

at all and can simply rotate each phone appropriately relative to them, then

determine whether the phone lies within the closed curve determined by the

vertices.

4/2/03

Calculation of

acceptance with refraction

calcAcceptanceRayTrace.m

plotAcceptanceRayTrace.m

calcAcceptanceRT.m

With

refraction, the ocean is not isotropic and we must actually rotate the whole

disk, leaving each phone fixed.

Again we do this phone-by-phone.

In this case each circle of the radiation disk is bent by

refraction. Each ray bends

vertically and lies in a vertical plane.

So instead of choosing the plane that cuts the disk perpendicularly, we

choose the plane (through the phone – interaction point axis) that is

vertical. This plane generally

cuts the disk obliquely, not perpendicularly. So we must first determine the vertices of this oblique

cross section. We can then bend

the rays within this plane, because it was chosen to be vertical.

To

determine the oblique cross section, we transform each vertex of the original

(perpendicular) cross section.

Consider each pair of vertices that determine a circle of the radiation

disk. These two vertices are

transformed by determining the intersection of the circle with the vertical

plane.

Once

we’ve determined this cross section, we bend each ray ending on a vertex

to determine the oblique cross section of the refracted disk. We can then determine whether the phone

lies inside or outside this set of vertices, as before.

Note

that the determination of the original cross section through the radiation

pattern, and the bending of rays, must be done separately for each phone. Due to the many rays that have to be

traced (~ 100 per phone, so ~700 per neutrino interaction), counting hit phones

with refraction takes O(100) times as long as without refraction.

This

strategy was implemented but was exceedingly slow, so slow that it took

multiple CPU-days to get the Monte Carlo integration to converge. Only after implementing this method and

realizing that it was too slow did I realize there was a simpler method.

4/7/03

Calculation of

acceptance with refraction in 1D instead of 2D

findRay.m

traceRaySetDepth.m

plotDiskVerticesPolar.m

calcAcceptance1RayTrace.m

The

method described above requires, for each phone, sampling rays in a vertical

plane to determine a 2D cross section of the radiation disk, then determining

whether the phone lies inside the cross section.

A

simpler method involves determining, for each phone, the single ray from neutrino interaction to phone. We then only need to determine whether

the ray reaches the phone in a short enough path length that it is still within

the radiation pattern.

The

first step of this method is determining a ray between two arbitrary points,

the source and the receiver. This

is implemented in findRay.m. This

is unfortunately not a direct calculation but involves an iterative

solution. Direct calculations can

be made to trace a ray emitted from an arbitrary point at an arbitrary angle,

but it is not generally known a priori which angle the ray should be emitted at to reach the receiver

position.

The

general ray trace problem (from an arbitrary point at an arbitrary angle) only

has two inputs: source depth and initial angle (we assume the sound speed does

not vary horizontally). So to

solve the source-receiver problem we trace multiple rays with multiple initial

angles, from the source depth to the receiver depth. The range (horizontal distance traveled) is determined for

each of these rays. The ray we

seek is that ray with a range equal to the horizontal distance between the

source and receiver. We implement

this with a least-squares algorithm, seeking the initial angle that minimizes

the difference between the desired range and the ray range squared.

findRay.m

determines the initial angle and the path length of the single ray from source

to receiver. The next step of this

method, once we have the ray length and angle, is to compare it to the

radiation pattern. The ray

represents the path of an arbitrary sound (not necessarily a neutrino) of

arbitrary amplitude. We must

determine whether this path is short enough to lie within the neutrino

radiation pattern at the emitted angle.

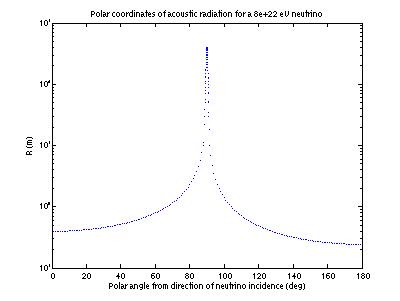

We do this by using a lookup table for the disk vertices (as shown in

Figure 3) in polar coordinates. An

example of this (for the same energy as Figure 3) is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

All

of the vertices necessary to represent a disk in rectangular coordinates (such

as that in Figure 3) are contained within ~1 degree. That is, the radiation lobe is confined to a width of 1

degree. This means that direct

conversion of the vertices in Figure 3 to polar coordinates is inadequate. The vertices in the rectangular plot

had to be supplemented before conversion to polar coordinates, in order to

determine the behavior of R(theta)

at the other 179 degrees. This was

done by assuming the radiation disk crosses the y axis perpendicularly. If this is the case, R(theta) is as follows

h1/cos(theta), 0

< theta < pi/2

h2/cos(pi-theta), pi/2

< theta < pi,

where h1 is the vertical distance of the first y intercept

above the origin, and h2 is the

distance of the second y intercept below the origin. These values were used for theta at every integral degree

from 0 to 89 and 91 to 180.

The

behavior of R(theta) in this

interpolated region is important, and we should verify the assumption that the

radiation crosses the axis perpendicularly and we can interpolate it from the

nearest vertex to the axis.

From

the azimuth and zenith of the neutrino, and the initial angle of the

neutrino-receiver ray, it is straightforward to determine the initial angle

between the ray and the direction of incidence. This angle is exactly theta in our radiation pattern plot (Figure 4). The geometry involved in determining theta is much simpler than what was necessary for the

planar method. Once we know theta

and the ray path length (s), we

simply look up R(theta) for the

appropriate neutrino energy. If s

< R, the ray reaches the receiver

while still inside the radiation envelope, and the neutrino is detected by the

receiver.

This

method assumes that the acoustic signal depends only on the initial ray angle

and total path length, not on the amount of refraction. That is, we assume the signal is

neither scaled nor distorted by refraction, as it might be.

4/7/03

Comparison of run times

Roughly

1e5 Monte Carlo points (independent random choices of neutrino x, y, z, theta,

phi) are necessary for convergence of the acceptance calculation. We have calculated acceptance with

three algorithms:

1) Assume no refraction; rotate phones with fixed 2D

rectangular disk coordinates

2) Assume refraction; rotate 2D rectangular disk

coordinates with fixed phones

3) Assume refraction; determine the single ray from

neutrino to each phone

Table 1 gives a comparison

of run speed and total run time necessary for the three algorithms (on a single

CPU). Algorithm 3 is the best

so far considering both accuracy (accounting for refraction) and speed.

Table 1

4/8/03

Results of acceptance

calculation

calcAcceptance1RayTrace.m

plotAcceptanceRayTrace.m

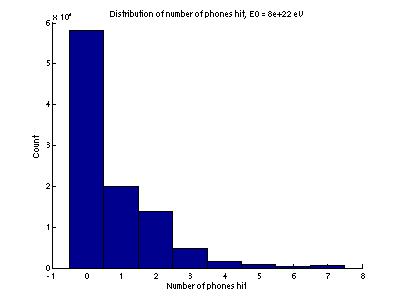

The

algorithm described above (calcAcceptance1RayTrace.m) was run for energies 2e21, 4e21, 8e21, 2e22, 4e22,

and 8e22 eV. Distributions rae

given below for the highest energies.

105 Monte Carlo points (x, y, z, theta, phi) were generated,

and the number of phones hit by each event were counted. Figure 1 gives the distribution of the

number of phones hit.

Figure 5

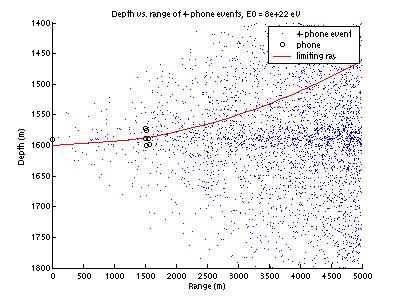

Figure

2 gives a side view of the distribution of 4-phone events. We are using an SVP from the day of the

light bulb drop. This SVP extends

to 1800 m depth. We have generated

points from 1400 m to 1800 m (even though the sea floor is at 1600 m; we ignore

it for this step). It is unclear

why there is an excess of points in the plane of the phones. We might expect such an excess not

exactly in the flat plane but bent upward by refraction. The red curve represents a typical

refracted ray in this region. It

was emitted horizontally from 1600 m depth.

The

next step is to appropriately account for the sea floor. The events plotted in Figure 6

represent those detectable by a detector at the same depth as the SAUND

detector, but with the sea floor 200 m lower than it actually is. Events below the red curve will

typically hit the sea floor and will not actually be detected. Properly accounting for the sea floor

will remove roughly those events below the red curve. It appears this will reduce our acceptance by a couple

orders of magnitude.

Figure 6

Figure

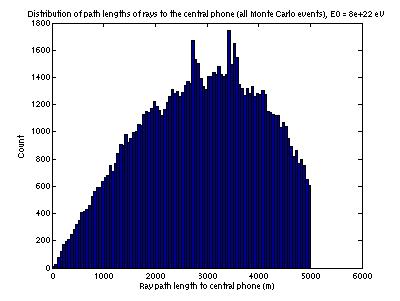

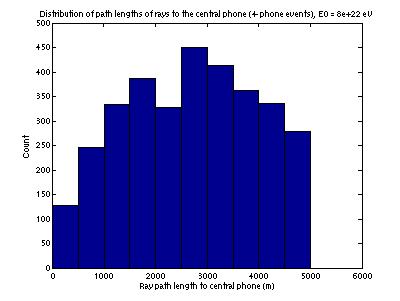

7 gives the distribution of path lengths of (refracted) rays between each Monte

Carlo event and the central phone.

It is cut off at 5 km, the radius at which we have chosen to cut off our

effective volume. Beyond this

distance two effects make event reconstruction difficult; (1) refraction

becomes an even stronger effect and (2) points that are not very close may have

similar time differences of arrival (position reconstruction uncertainty

increases with range). The first

effect is independent of the detector spacing; the second is determined by

detector spacing.

Figure

8 gives the same distribution, but only for those events that trigger 4 phones

rather than for all events generated.

Figure 7

Figure 8

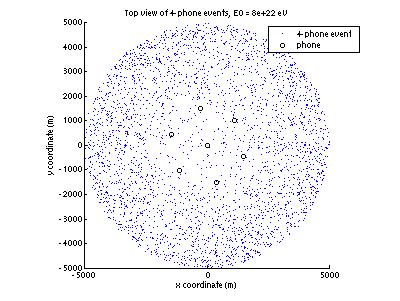

Figure

9 gives a top view of those events that trigger 4 phones or more.

Figure 9

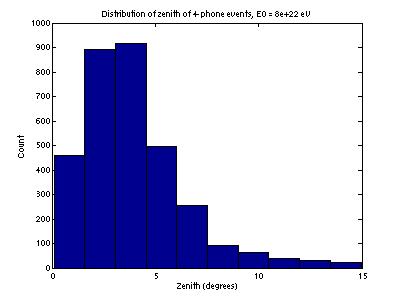

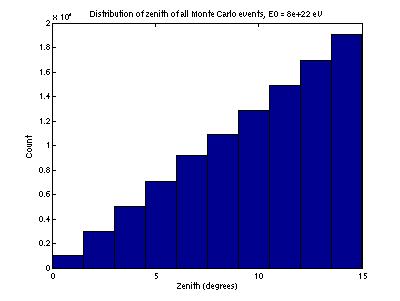

Figure

10 gives the distribution of neutrino zenith for 4-phone events. Figure 11 gives the same distribution

for all generated events. They are

generated isotropically, but only those near vertical are detected.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure

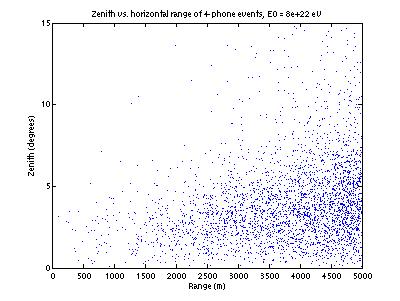

12 shows zenith vs. range of detectable events. As the range increases, the maximum detectable zenith

increases.

Figure 12

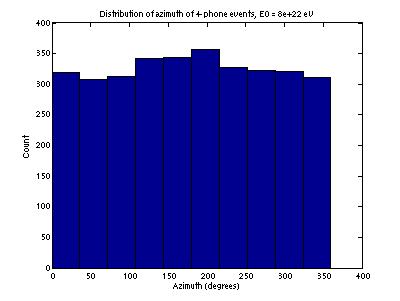

Figure

13 gives the distribution of neutrino azimuth. Detection appears to be independent of azimuth.

Figure 13

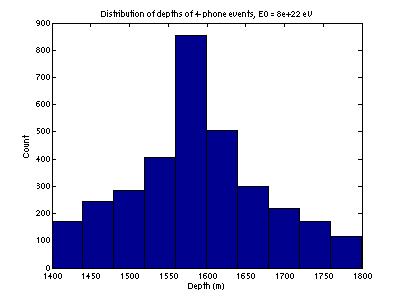

Figure

14 gives the distribution of depths of detected neutrinos. The limits used for both zenith and

depth in the Monte Carlo integration were not quite large enough and will be

extended.

Figure 14

4/8/03

New acceptance curve

calcAcceptanceRT.m

plotAcceptanceVsE0.m

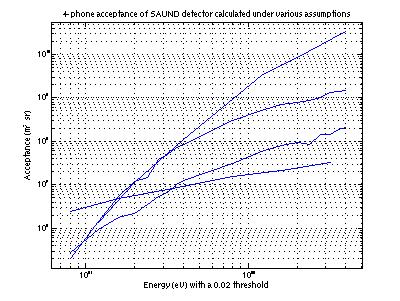

Figure

15 presents the new acceptance curve in addition to previous ones. The top three curves represent those

calculated neglecting refraction.

The top one assumes infinite homogeneous water; the middle one limits

our effective volume at 10 km; the third limits it at 5 km. The bottom curve includes refraction

and limits the effective volume at 5 km.

It is lower than the initial curve by 3 orders of magnitude at high

energy, but is actually higher by one order of magnitude at low energy. I’m not sure why this is; perhaps

the curvature induced by refraction is somehow beneficial at lower energy.

The

curve will lower even further when we include the shadow effect of the sea

floor.

Figure 15